When our Churches Raise their Eyes…

One of the principle questions about the strength or weakness of the Church across history, is the question of whether or not Christians of various different confessions are able to successfully stand against the aggression of evil in this world. To answer this question is far from simple, if not only because, for centuries, Christians themselves have been unable to fully cope with the internal evil of division in a Church torn apart by different teachings about the faith, as well as different confessional, national and even political divisions. These things – along with Christians’ inability to truly embody the Gospel teachings on peace, love and freedom – are often real blocks. As Nikolay Berdjaev wrote, “it is the most difficult thing of all to embody the religion of love, but this doesn’t make the religion of love itself any less lofty or true.” This hardest-of-all-to-embody religion of love is alive and well in the world, and every contemporary example of Christian love, itself standing against hate, is precious.

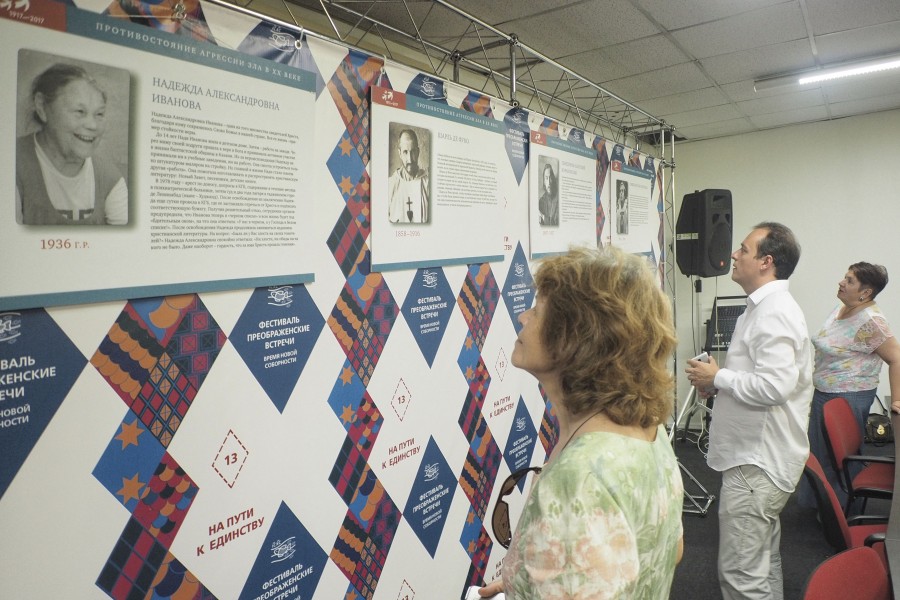

At the 3rd Annual International Transfiguration Meetings Conference, which took place in Moscow on 19-20 August and was dedicated to the theme Time for a New Sobornost, Christians of various confessions came together in the Path to Unity Pavilion, to share with each other examples of this sort of Christian love, which stands against hate in our world.

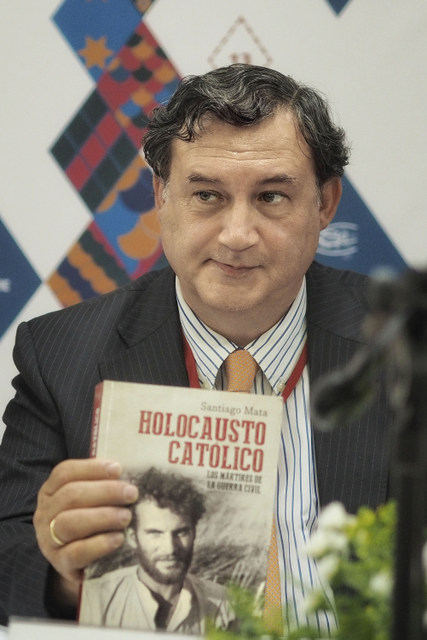

Santiago Mata, a journalist from Madrid, spoke about the “Catholic Holocaust” which took place during the Spanish Civil War, in the 1930s. “People willing sacrificed their lives, and some of the martyrs used this word (“holocaust” – Fr.Georgy) in their letters. The blasphemous desolation, which befell the Spanish church of that time, was of such scale, that the delegate from the Spanish “Red Party”, when sent to participate in a congress of the godless in Moscow, could tell his comrades, “Spain has gone far beyond the Soviets and what has been accomplished by them, because in Spain, the church is entirely destroyed.” In today’s Spanish church, 1706 saints of the Spanish “holocaust” have been beatified, although in Mata’s opinion, these beatifications are happening too slowly, and this is being done on purpose. “In an effort to forgive evil, we have forgotten good,” he says. There is fear within the church, he says, that the beatification of martyrs will issue in a desire to accuse the killers and avenge this wrong. For this reason, the memory of and prayerful devotion to these martyrs is less than it might be among the common people.

The leader of the Society of St. Egidio in Russia, Alessandro Salakone, told us about the bitter conditions during the war in Rwanda, where during the animosity between the Hutu and Tootsie people, in the course of 100 days, nearly 1 million people were killed – a whole sixth of the population of the country. He told us of the Roman Bible kept in the Church of St. Bartholomew, “that Bible belonged to a single seminarian, who during the genocide didn’t want to separate from seminarians, who were of a different ethnic background, when soldiers came in and delivered a message, saying ‘you Hutu, get up and go now, and we will save you from the Tootsie.’ But the Hutu did not want to go. They did not get up. And they were killed them like animals, all the more because the entire genocide in Rwanda was a genocide of the sword.” The Society of St. Egidio was well known for its peace keeping efforts on Mozambique, Kosovo, and other places where there was war. They gathered together in one small community of warring tribes in Rwanda, to serve as the leaven of a new, peaceful society.

“We looked for those who both in times of peace and in times of war aren’t bothered by questions of ethnicity. These were children without guardians, the poor…people who, unfortunately, suffer in the same way both in times of war and in times of peace. We gathered these Christians around the idea of reconciliation in order to build a future. I think that this same sort of logic could be used in by Christians of different Christian confessions in Europe today. In the end of all things, Christians become united not when they look at what is in their own field, but when the really have a look at what is going on around them. Today, for instance, the Christians in Syria and in Iraq are suffering. When we raise our eyes and have a look at what is going on around us, there is far less time to argue between ourselves,” said Alessandro Salakone.

The last hundred years of history show, with bitter obviousness, the necessity for a new, conscious Christian unity – as an embodiment of the Church’s mission to witness to this world, which has been rocked in an unprecedented way spiritually, socially, and politically. Already in the 1930’s, in her thoughts about sobornost, Mother Maria Skobstova wrote in the journal entitled An Orthodox Affair, “The world has entered into catastrophes which seems apocalyptic, and we still don’t know their meaning…but we know one thing. Christians have no right to protect themselves from the storm and to hide in sheltered places. The Church, itself, is called to be a place of shelter for pilgrims – an “Ogiditria” – and the guide for humankind. She herself is the only one who can provide answers to the issues from which humankind is suffering.”

In another article published in the same journal, Mother Maria is quoted as saying, “a religion of personal salvation as the central goal of Christianity is foreign to us…it is obvious to us that Christ came to save all of us, and the individual person amidst the masses. It is obvious to us that no single person is the body of Christ but that rather, his body is made up of all His humanity, knit-together in a community of all the members of his Body. Sobornost gives us the rock-solid foundations for social work within Orthodoxy.”

From the stories of festival participants, it is obvious that the same principles are guiding Christians from the Road to Lovingkindness fund from Nizhnevartovsk, and the international Christian charity called Barnabas, who have worked with orphans in India, Burma and Nepal, and who have, for more than 20 years, aided persecuted Christians, communities and churches from various countries.The coordinator of the Barnabas fund, pastor Fyodor Mokan, from the Baltics, spoke of this saying, “more than 200 million Christians are suffering from various sorts of discrimination today, while 100,000 per year add to the list of those who have been killed for their faith. In the course of half an hour – that is the approximate time of our meeting here – 18 more people will be martyred for their faith.”

Pierangelo Torricelli, Head of the Associations of Italian Christian Workers, spoke about one of the most poignant modern problems – the battle with the Mafia. Pierangelo recalled the words of Judge Giovanni Falconi, who died at the hands of the Mafia in 1992. Speaking to a journalist, the judge said that the Mafia is a phenomenon fully human, social, political and economic – which means it can be defeated. “Historically we have seen the sad example of cooperation between the Mafia and the church as, for example, when in southern Italian cities, during times of religions pilgrimage, church clergy have bowed before Mafia bosses. Other Christians – primarily Waldensians – over the course of many years, have been judgmental about the presence of the Mafia, which is, by the way, an outstanding sign of unity between all Italian Christians. It is absolutely necessary that all the churches together take responsibility for this social problem, and this, itself, can become a basis for unity.”

One effective means of standing against the Mafia is the Libera (Freedom) association, founded by Don Luigi Ciotti, which helps drug addicts in recovery. Libera was initiated under a law, which allows the property of Mafiosi to be confiscated and appropriated by charities. So, for instance, the harvest from previously owned mafia lands is sold in inexpensive shops, helping the common people to see and reap the reward from the absolutely legal battle against the Mafia.

“It is important to remember the foundational values of the Gospel,” said Pierangelo Torricelli, in conclusion. “This is true because, in the first instance, it is Christians who should resist against any sort of tolerance, submission, blackmail or ambiguity – demonstrating their faith in doing so. Christians, more than others, should feel that silence and indifference actually enable all sorts of criminal behavior.”

In her summary conclusion of the various topics under discussion, the discussion leader, Larisa Musina, who is Head of the Scripture Department at SFI, thanked all the participants for their examples of creative and daring action against the aggression of evil, saying, “this is especially important for our country, because the forces of evil have been so great in our country over the last century, that people have begun to feel completely helpless in front of them.”

***

One of the more interesting conclusions of our meeting was a letter from one of the participants, mentioned above – Santiago Mata – to the General Director of Aeroflot Russian Airlines, Vitaly Savelev. In his letter, the Spanish journalist asks the Aeroflot Director to think, long and hard, about the symbolism of the company emblem, the hammer and sickle.

Specifically, Mata writes, “the emblem on your employees’ uniforms and even on the baked goods you pass out on flights, prolongs the presence of dictators who caused your country endless suffering – both in the minds and in the lives of your customers. I am sure that many of your employees have lived through communism themselves or through their parents, and you are not allowing them to free themselves of the mark of this heritage, which is like a stamp from a concentration camp on their forearms. How is it that you can make people wear the hammer and sickle on their caps, their badges, and on the cuffs of their uniforms – at the same time imprinting this symbol within their heads, their hearts and on their hands – as if, all the time, reminding them that they have been slaves, and not taking any interest in whether or not they will ever be free? I sincerely hope that I am mistaken, but at the very least let us, your customers, be free from the hammer and sickle when we eat our baked goods on your airline, because what I ate, at least, I believe will not be digested in my stomach. God will judge us all, but there is still the history of your nation, which might either include you as one of those who have done a service for dignity to the citizens of your nation, or might otherwise erase your name in contempt, if you choose to do nothing.”

Oleg Glagolev

Photo: Boris Levitsky