Is “sobornost” possible in today’s church?

Participants in this year’s “Transfiguration Meetings” considered impediments to the continuation of the living tradition which was cut off by the Revolution of 1917, as well as factors that would enable its continuation.

The third international Transfiguration Meetings Festival was themed “Time for a new sobornost”, and dedicated to 100th anniversary of the 1917-18 church council, which was unique both in terms of its participants and in terms of its decisions, many of which have yet to be put into effect in church life.

How do we continue a tradition that has been broken – not so much in form as in spirit and meaning? How do we renew not only the activity of the church structure, but the Christian life, itself? These were the questions being fielded by the participants of this year’s forum: laity and priests, historians, journalists and writers, artists and representatives of various Christian movements across Russia, Italy, France, Germany, the US, the Czech Republic and Latvia.

It isn’t about Patriarchy, but about “sobornost as a guiding principle”

“When we consider the Council of 1917-18,” says Historian Ilya Soloviev, “the main thing we note, is the decision that sobornost should lie at the foundation of church life, and that sobornost should be the guiding principle within the church. This is the primary significance of the Council, and its only contribution which was untouchable by the historical events that were to follow immediately afterwards.” Although “many of the other decisions of the Council were put off, declared invalid or distorted, it is this idea of “sobornost as the church’s guiding principle” that remains, and that imparted to the Council its particular “taste” and its authority,” said Fr Ilya.

He underscored the fact that no single part of the system of higher church management created by the Council “has any merit on its own strength”, and that the system as a whole, during the period of Stalinist dictatorship, for instance, “didn’t work as had been envisaged by Council participants, nor could it have.” Integral, practical application of the Council’s decisions “has nowhere, ever been seen in the history of the church, because the system that was created by the Council, was designed for use in a free church in a free country, and over the course of the next 100 years, Russia was not a free country, nor was the church in Russia a free church.”

“During Stalin’s time it was possible to construct systems for the church, for instance the establishment of a High Council for the Church, to introduce regional metropolitans and even bring back the election of bishops, for show. The patriarchate was restored to the church. Basically, it was possible to observe all the form. But the church wasn’t free, and nor was the state – and under these conditions the system could not work as originally intended,” the priest said.

In Fr Ilya’s opinion, the hardest question is whether or not the decisions of the Council of 1917-18 can be put into effect in a way that is not just “for show”. I think that if a free state arises in Russia, and if a free church is separated from that free state – if the church is allowed to develop according to its own law, which is not dictated by anyone else – then I think it is possible that a portion of the decisions taken by the Council can acquire their practical significance in the life of such a church,” said Fr Ilya.

The Council of 1917-1918 hasn’t been properly closed

The spiritual father of the Transfiguration Brotherhood and Rector of St Philaret’s Institute, Fr Georgy Kochetkov, noted that “not only was the Council outwardly blocked, but it was also inwardly contradictory.” For this reason, its decisions – although they haven’t been overturned by anyone – have not become manifest in life, that is, they became “valid, but were not active – at least for now. Perhaps people will look back to the Council in future, and perhaps those people will finish it’s work.”

In Fr Georgy’s opinion, “the Council has still not been properly closed; its church hasn’t adjourned it.” For this reason, it is important “not only that we accept its rulings, but also that we understand that, in some miraculous way, the Council still continues today. We have paid too much for the last hundred years of our history, and everything that has been achieved over the last hundred years needs to be properly made sense of and, in fullness and integrity, rolled into our continuation of the Council,” he said. “Most importantly, we must, once and for all, admit that the Constantinian era of Church History is over. The post-Constantinian era is upon us whether we like it or not, and we need to be able to describe it, as well as perceive and make proper conclusions in light of this fact.”

In search of a new sobornost

Dmitry Gasak, Chairman of the Transfiguration Brotherhood, pointed to the problem of the break in church tradition during the 20th century. “The Council’s decisions haven’t been overruled by anyone – they continue to be in force in law, but we both feel and see that these decisions are not active,” he said. Despite the fact that the Council’s decisions were published, in this, the 100th anniversary year of the Council, “for the most part, only the restoration of the patriarchate is discussed.” In Gasak’s opinion, the Council’s decisions are not internally in demand within the church. “Demand for the Council’s decisions does not arise, because the people of the church don’t really form a community.”

“Who are the people of the church? The church itself doesn’t yet know,” said Gasak, underscoring that the “restoration of continuity is something spiritual and cultural, and not only legal. We don’t think in the same way as those who have gone before us. We have canonized them, but can’t understand how they thought or what they were striving for in the church. They are foreign to us,” he explained, “and when we speak of a new sobornost, we are speaking of the desire that Christian Tradition become living tradition, received by us in all its full historical depth.”

He added that the experience of the Council of 1917-18, which “happened but whose rulings were not taken up in life”, and the experience of the Council of Crete in 2016, which “convened but didn’t take place in the same quality as originally intended,” go to show that we view and place our hope in “councils”, defined only as representative authorities made up of gathered church hierarchy, while limiting the institute of sobornost to such a definition is impossible.

“It is impossible to successfully barricade the human person”

One attempt to renew the beginning of sobornost and solidarity within church and society is the “Calling our Nation to Repentance” initiative, started by the organizers of the Transfiguration Meetings in this, the hundredth year since the Revolution of 1917. The initiative calls upon people with live consciences to stand up and take responsibility for the Russian catastrophe and the evils of Soviet era, searching together for the means to free our people from the sins of the past. Speaking at the “Calling our Nation to Repentance” festival pavilion, Fr Georgy Kochetkov underscored the importance of those steps taken by each individual person: “We are an exceedingly small group, but history has never been made by the masses. It is not possible to wait for something to be said from above because everyone is fearful of everything and there is no trust between people. We have to search and investigate for something that cements our society together, beginning with foundational questions about good and evil and ending with the most concrete and tangible things. Action from below is extremely important, and even if everything is blocked at present, with strict control over information, culture and education, it is impossible to successfully barricade the human person himself, if there is something going on inside of him. Pulling together our strengths – people of like mind and soul – we need to do that which will enlighten our lives.”

The topic of sobornost was also pervasive across the 13 festival pavilions dedicated to different aspects of church life, among which were: historical memory, the problem of fellowship in the church, adult catechesis, children and youth, liturgical service, and participation of laity in the life of the church.

Representatives of various volunteer movements, including: Starost v Radost (From Old Age to Joy), Beloye Delo (The White Affair), the “Danilovtsy”, the Civil Assistance Committee and others, shared their experience of “action from below” during a session entitled “Community and Fellowship.” “Everything started with one trip to Pskov, in search of folklore,” explained Olga Balashova, a representative of Starost v Radost. Our fellowship with the elderly women became the foundation for all of our later work.” Many volunteer movements which arose out of simple caring are not only well-known today, but have real weight of authority within society. Their voices are heard, and their representatives have meetings with various state committees and commissions.

Christians against the aggression of evil

At the inter-confessional pavilion named On the Path to Unity, representative of the Italian Christian movement ACLI (Christian Associations of Italian Workers), Pierangelo Torricelli spoke about the unique battle with the Italian mafia – that “state within a state, with its own structure and laws”. The ACLI sees the enormous chasm between the people and the state in Italy as one of the reasons for the mafia’s appearance. The mafia proposes easy solutions to problems that are difficult to solve through government structures. For this reason, one of the ACLI’s initiatives is focused on bringing the state and the people closer together by, for instance, providing assistance in the declaration of income. The ACLI also tries to get laws past which allow the confiscation of mafia property, allowing the property to be passed into the hands of society for public use. For example, a vineyard, villa and land taken from Mafiosi, have been given to the local city and provide opportunities for employment for young people. This gives people positive incentive to battle against the mafia.

“This bears witness to the action of Italian Christians in Italy, and this is especially important in Russia, where people ran into such volumes of evil during the 20th century, that they feel entirely unable to take on this aggression. It is very important that Christians should be able to gather together in battle against evil and prevail,” said one of the pavilion organizers, Larisa Musina, who is the Head of the Scripture Department at St. Philaret’s Institute.

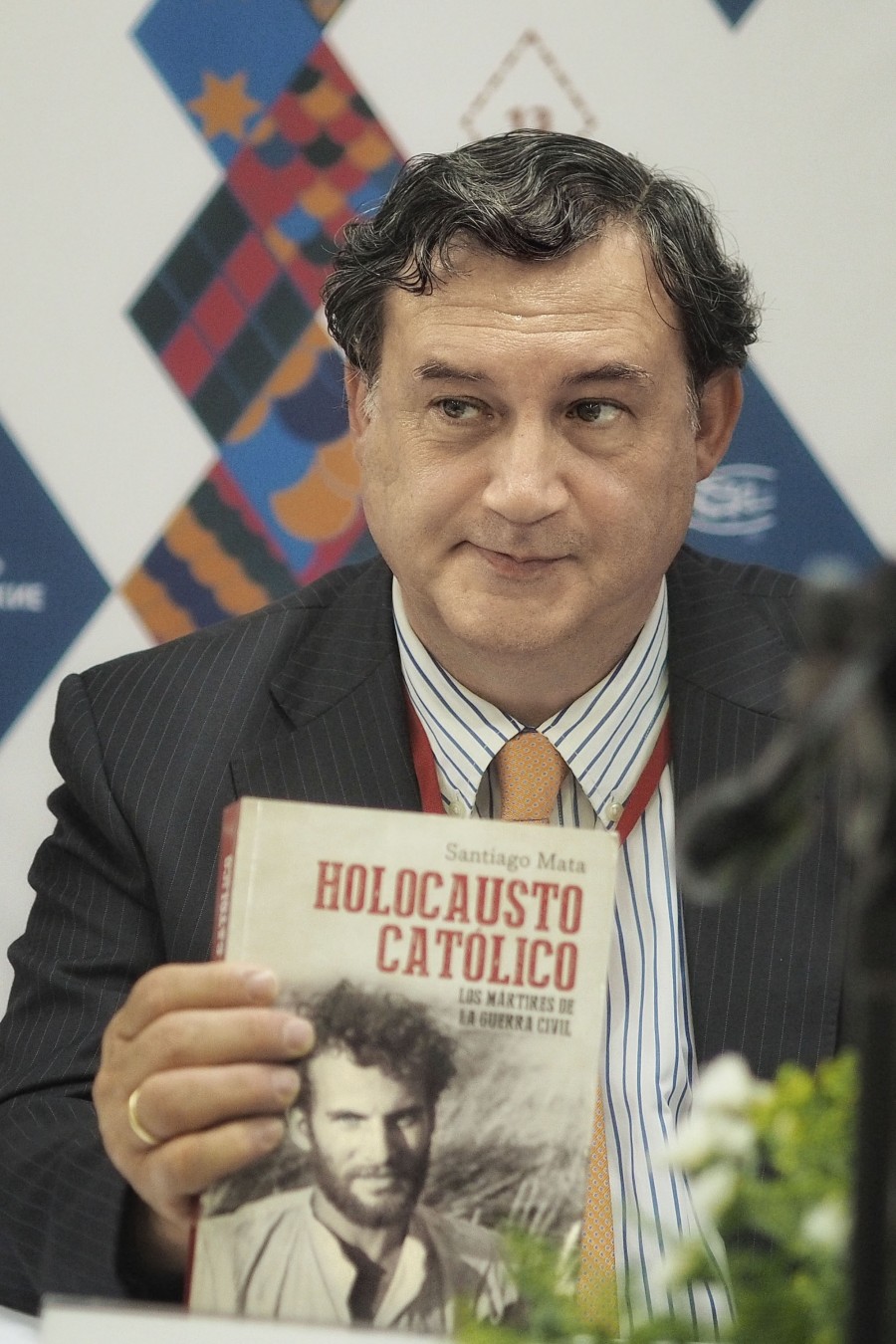

At the On the Path to Unity Pavilion, in which representatives of various church movements from Italy, Spain, France and Russia took part, Santiago Mata, the author of a book entitled “The Catholic Holocaust” and other books on the history of the Spanish church, spoke about various responses to the aggression of evil – in particular in the case of various religious “man hunts” during the time of the Spanish Revolution of 1936-39. Mata spoke of the way in which bishops, the Pope, lay people and others, who became martyrs for their faith, responded to the aggression of evil during this time.

As has become traditional, many of those who participated in the Transfiguration Meetings attending liturgy and took communion at the Christ the Savior Cathedral on Sunday morning. In welcoming members of the Transfiguration Brotherhood, the sacristan of the Cathedral, Mikhail Ryazantsev, noted that the Sunday following the feast of the Transfiguration of the Lord is one of the three days during the year – the others being Pascha and – when such a great number of faithful fill the church for Sunday liturgy.

More than 2000 people took place in this year’s Transfiguration Meetings, including:

First Deputy Chairman of the Synodal Mission Department, Abbot Serapion (Mitko), Member of the Patriarch’s Council for Culture, Fr Nikolay Sokolov,

Head of the Department of Church History at the St. Petersburg ROC Seminary (Dukhovnaya Akademia), Fr Georgy Mitrofanov, Member of the Metropolitan of Anthony of Sourozh Heritage Fund, Elena Sadovnikov,

Leader of the Russian Chapter of the Dvorjanskoye Sobraniye, Oleg Scherbachov, Director of the Social Research Methodology Center of the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, Dmitry Rogozin, Film Directors Andrey Smirnov, Alexander Kott (“The Fort at Brest”, “Christmas Trees” 2, 3 and 5, and “Diamond Hunters”), and Daria Violina (“Longer Life”), Creator and Director of the “Takiye Dela” Information Portal, Dmitry Aleshkovshy, Writer and Translator Nikita Krivoshein, as well as priests, journalists, writers, well-known independent artists, and representatives of Christian organizations from Russia, Italy, France, Germany, the US, the Czech Republic and Latvia.

Sofia Rudakova, Sofia Androsenko

Photography: Alyona Kaplina, Alexander Volkov, Diana Rybakova, Boris Levitsky

For Informational Purposes:

The local council of the Russian Orthodox Church which was convened on 15 August, 1917 in Moscow, was the first, full local council that had been held in 217 years. Around 600 people took place in the work of the council, half of whom were lay people, including church intellectuals and scholars.

Among the main decisions of the Council was the restoration of the Patriarchate and agreement on a new system for organizing church life, which envisaged the enablement of broad initiative “from below”, and the establishment of close contact between the faithful and their pastors at every level. The Council introduced the principle of elected diocesan headpastors (bishops) and lifelong terms for these bishops, together with the requirement that they not be moved from sea to sea “except in exceptional cases requiring extreme measures”, and affirmed the broad rights of the council of bishops. Mission and preaching – including mandatory sermons at every liturgy – were entrusted to all clerics, even of the lower ranks, as well as to lay people who were specially dedicated to the Church and specially prepared to bear this responsibility. “Evangelistic brotherhoods”, which the Council called upon lay people to establish, were to aid in the development and enlivening of preaching, in general.

The institution of Parish By-Laws, which was introduced by the Council, included a parish roll of each person by name; restored the ancient norm for participation in the liturgy (not less frequently than once every three weeks); restricted bishops’ rights to move or lay-off parish clergy; gave the Parish Council broad rights in the sphere of organizing parish life, including the planning and control of financial activities and management of parish property; and broadened women’s opportunities for participation in liturgical life, preaching and church management. The Council sanctioned the use of Russian language in church services if a parish should request and the local bishop grant his blessing to worship in Russian.

The weakest aspect of the Council was in the area of church-state relations. At the same time as demanding its own independence, the Council could not come to terms with breaking links with the state that had supported the church for such a long time. The council’s definition “On the legal position of the Russian Orthodox Church”, which was passed on the 2nd of December, 1917, seemingly purposefully ignores anti-church decrees and the establishment of a new power and authority in Russia. Despite the coup in October 1917, the Council doesn’t call for armed rebellion against the Bolsheviks, doesn’t lay an interdiction on those cities where are caught up in revolutionary rebellion, or make a clear pronouncement judging the spiritual natural of the new government.

The work of the Council was curtailed by civil war and repression of the church. Thereafter, one in ten participants of the Council was recognized as a saint of the church. Half of the delegates were shot, died in exile, or spent time in labor camps.