Being Good Theological Neighbours

A song about loving the Volga River suddenly starts playing. It’s typical enough to the Russian ear – but this time it’s in German. These days, the word “Germans” together with the word “Volga”, more likely than not call to mind memories of difficult battles in the Second World War. It almost seems as if these recollections have become part of our genetic code and are passed from generation to generation as part of a particular strand of our DNA. But, as it happens, this particular song was written by Germans; Germans who lived in this land long ago, when the relationship between our two nations was very different, and free from more recent strains.

The festival event “Russians and Germans in Russia: Landmarks in History and Theological Good-Neighbourliness” was opened with the song about the Volga. This event, hosted by the Holy Archangel Brotherhood together with The Bavarian Cultural Centre for Germans from Russia, was one of more than 30 events at the annual Transfiguration Meetings Festival in Moscow – this year dedicated to the theme “A Time for Peace”. On the improvised stage stand the Tretyakov (Mejder) family – Volga Germans from tiny Sarepta, to the south of Volgograd. These distant relatives of Nelli Andreevna Mejder were among those Germans who settled on the Volga at the end of the 18th century – a religious community of Hernguters. Since that time, nearly 15 generations of Mejders have made their home on this land, and come what may, they still live and work the land there to this today.

“My parents, as goes for everyone in Sarepta, were real Russian patriots,” explains Nelli Andreevna Mejder. “And despite being exiled (our family was deported to Kazakhstan after the start of the Second World War), despite repression, and other difficulties (all of us were labelled “traitors” after the start of the war), they stayed patriots. Believe me, these are not empty words…for the entire duration of our life in exile, my mother dreamed of going back. This was their land, their forefathers lived here, and made their home a beautiful place… they really created something of otherworldly beauty.”

Sometimes it seems that the 20th c. forced our two nations apart, to the opposite sides of the barricades, in a way that is insurmountable. Sometimes the divide ran right across the very fate of a particular person. Can we heal what has happened? Does the theological good-neighbourliness hailed in our event title really exist? And how can we live so that it becomes evident? Does a nation have a particular “personal” fate before God? Are there nations which can – by God’s will – live together? Our festival guests gathered to discuss these and other difficult questions.

“Our festival bears the title ‘A Time for Peace’, but we are talking here not about the type of peace that can be won through diplomatic relations, but the kind of peace which is a gift that comes from above to fulfil us,” said Fr. Ioann Privalov, in his address which opened the festival event. “And suddenly we are able to welcome, in fellowship, a person who we were previously unable to welcome. In a stranger, totally unknown to you, suddenly you find something native – as if he is family.

It is in this type of peace that we have come together to look upon each other and emerge ourselves in the history of this festival event’s participants. In this spirit of peace, we need not forget anything – in fact, on the contrary we can remember both the tragic and the bright side of our historical relationship, in all its fullness. This is very important, because in the words of our meeting’s participants, there is some sort of inexplicable mystical link between our two nations.”

“Our life is determined by meetings,” said Pastor Anton Tikhomirov, Doctor of Theology and Rector of the Evangelical Lutheran Seminary in St. Petersburg. “Some of these meetings are extremely deep and become real markers in the pages of our lives, even determining something of its essence. When such meetings occur, we get to know another person and we come to know ourselves. New relationships are born, and this is the true nature of good-neighbourliness. It is remarkable to me that such meetings can take place not only between individual people, but also between nations. The history of Germany and Russia together is full of such meetings. They have been very diverse, even sometimes tragic – but for the most part our meetings have been fruitful, mutually enriching, and full of mutual respect.”

There are many books, unfortunately read by too few people, which bear eloquent witness to the fact that Russia and Germany were once much closer than we can ourselves imagine. Olga Litzenberger, a PhD in History, professor and researcher for the Bavarian Cultural Centre for Germans from Russia, has written a number of works on the history of the Lutheran Church and of Germans in Russia. Litzenberger says that it is difficult to find two countries in Europe which are historically more tied together than Russia and Germany. Economic, cultural and dynastic ties have persisted over the centuries. Long ago, Russian tsars invited German master tradesmen of the most varied professions to Russia. Germans in Russia were prominent in the pharmaceutical, medical, mining, military, legal, architectural and building, publishing and other professions. Their descendants were the cream of the crop of pre-Revolutionary Russia’s technical, scientific, service and economic elite. We know of many societal activists, scholars, politicians and even Russian saints who have German roots: Barklay de Tolly, Sergei Witte, Fyodor Haas, Prokopius of Ustyug, Marina Tsvetaeva, Vasily Struve, Anna Herman, Vladimir Dal, Boris Rauschenbach, Ivan Kruzenshtern, Alfred Schnittke, Denis von Wiesen, and Fr. Pavel Adelgejm.

As is well known, Peter the Great established the tradition of intermarriage between the German and Russian royal families. He allowed Lutheran Charlotta to remain Lutheran, rather than adopting the Orthodox faith. All previous princesses had changed their faith-allegiance when intermarrying. The most famous Russian Empress – Catherine the Great – was also of German origin. When the agreement with future Emperor Peter III was reached, she made the strategic decision to study Russian history and language, and switch to the Orthodox faith.

The history of the relationship between our two peoples has, of course, not always been smooth. The great Battle on the Ice, between Alexander Nevsky and the Teutonic Knights rather sent things in a frigid direction, as did the Livonian War, Prussian encroachments and the fixing of Russia’s boarders after the Russo-Turkish War. As a result, frescos appear in Russia in which, for instance, a German merchant is pictured in hell, and the Council Code of 1649 forbids Germans from owning property if they are not Orthodox.

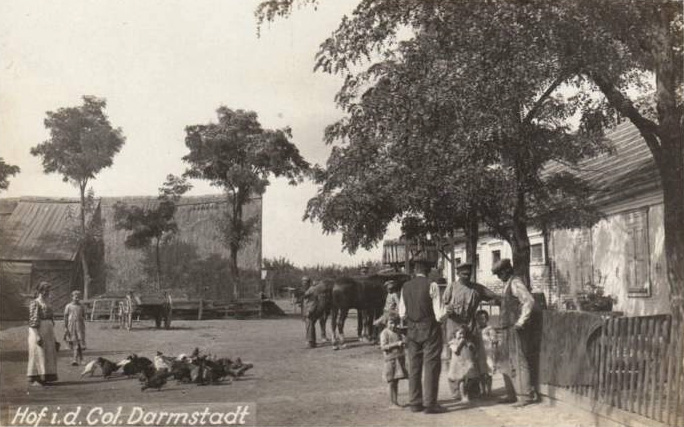

Nevertheless, the practice of inviting Germans to Russia remained current, right up until the beginning of the 20th century; in many larger towns and settlements there were even whole German districts. The manifest of Catherine the Great already mentioned above, according to which Germans were invited to settle and form a German colony on the Volga, had enormous significance in terms of the mutual enrichment of our two cultures. 30 thousand colonists came to settle at that time. The head of the Lutheran Church in Russia – which due to historical circumstance always felt more free and at home here than did the Roman Catholic Church – was the Russian Emperor himself (or herself).

Prior to the First World War, there were 2.4 million Germans living in Russia, and this was 1.5 percent of the entire population (which was 166 million in 1913 – now, for comparison’s sake, the population of Russia is 146 million). A majority of these became captives to their own heritage during Soviet times.

“One might say that the meeting between our two nations was purchased at a great price,” says Pastor Anton Tikhomirov. “And for this reason we can’t just give it up. Russians and Germans really have intertwined their cultures. This is true both externally and internally. We can speak of the deep interest of Lutherans to the Orthodox Faith, and vice versa. We can speak of the experience of cooperation between Lutherans and Orthodox, though we are not connected by doctrine or worship practice, though between Lutheran and Orthodox worship there is an amazing kinship which is evident in something quite primary. We are connected by our Lord Jesus Christ, and specifically because of this, our people who are of different faiths could unite and cooperate with each other during times of repression.”

Our guests from Sarepta sang not only of the Volga. They also sang a German spiritual song, “Jesu, geh voran”, which their ancestors sang when they were taken away for deportation on a barge, in 1941. Because no one explained anything to those on the barge, its passengers were sure they were going on a trip which would end with them being drowned…

At the beginning of the war, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR liquidated the German Autonomous Republic in the Volga region, and all Germans were deported, en masse. In order to achieve this, the NKVD moved into the Republic. Residents had 24 hours to show up at a meeting point. A total of 446 thousand Soviet Germans were deported to Kazakhstan, Siberia, and Central Asia.

After deportation, these people suffered hunger and the conditions of forced labour camps. Eventually some of them were able to return to Sarepta. But after the 1990’s, when the reestablishment of the Autonomous Republic was declined, Germans started to emigrate from Russia altogether. More than 2.5 million Germans left the country, and today more than 4 million Russian-speaking German citizens live in Germany.

Can we manifest a time of peace in ourselves today? Can we really work through the hardships that befell our two peoples at each other’s hands, and truly forgive each other? Our meeting here communicates hope in a real way, because here we have heard the voices of people with German roots who have searched for such a place of meeting and discussion all their lives.

“The history of our peoples is also a relationship of meetings,” said Pastor Anton, in conclusion. “These meetings are what determine our life and what determine us. We can meet with God and in God. Even the eternal life about which we dream is no static state, but a whole series of encounters with God – a series of meetings which form the direct continuation of those we are already experiencing, here and now.”